FAQs

Are CardioCommand products Latex Free?

How does transesophageal atrial pacing compare with alternative therapies?

TAP vs. external transcutaneous/transchest pacing.

Esophageal pacing is administered via the left atrium while transthoracic pacing is generally accomplished via stimulation of the ventricles. Atrial pacing is contra-indicated in patients with complete AV heart block. In patients with a functioning AV node, atrial pacing provides greater hemodynamic benefits compared to ventricular pacing (Topol et al). TAP is achieved with lower current (10-20 mA vs. 30-140 mA) and better patient tolerance compared to pacing from the chestwall (Alezedo et al, Madsen et al, Atlee et al, McEneaney et al).

A comparison of transesophageal rapid atrial pacing vs. transchest DC shock for terminating atrial flutter found similar efficacy between the two methods (Tucker et al); arrhythmias (3rd degree heart block, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia) were observed more frequently in cases receiving transchest shock (60% vs. 0%).

TAP vs. transvenous/endocardial pacing and recording.

TAP is administered via the left atrium while endocardial pacing is accomplished via stimulation of the right atrium. Rotter et al compared the two pacing methodologies for treatment of intraoperative sinus bradycardia and found nearly identical hemodynamic responses (heart rate, blood pressure, cardiac output). For evaluating sinus and AV node function, McEneaney et al and Cebron et al found no significant differences between electrophysiological parameters estimated by endocardial vs. transesophageal measurements. Samson et al and Favele et al compared TAP and intracardiac atrial pacing and found the methods to be equally effective in the diagnosis of supraventricular tachycardias. For evaluating atrial pre-excitation, Pehrson et al found TAP and invasive endocardial pacing to be equally effective at inducing atrial fibrillation and flutter in patients with a history of tachyarrhythmias. As compared to endocardial or transvenous catheters, insertion of an esophageal lead is clearly less invasive and faster to implement, and requires less technical expertise and no patient sedation. As CardioCommand esophageal catheters cost less than half of the typical endocardial lead, TAP is more cost-effective.

TAP vs. chronotropic drugs.

There are a wide range of pharmacologic agents for increasing heart rate in treatment of sinus bradycardia. Smith et al compared patients treated with TAP to 2 groups of patient receiving anticholinergic drugs (atropine, glycopyrrolate) and found that TAP produces more rapid and reliable heart rate changes than either drug. No significant differences in postoperative side effects were found between the 3 therapies. Tomichek et al studied hemodynamic responses of patients treated with TAP and gallomine and concluded that the ability to reliably and precisely control heart rate is superior with TAP.

TAPtest vs. exercise stress test.

For increasing myocardial oxygen consumption, TAP is an alternative to treadmill or bicycle exercise, particularly in patients unable or unwilling to exercise to their target heart rate. For diagnosis of one, two or three vessel coronary artery disease (CAD), Lambertz et al found sensitivity of stress-echo testing with TAP to be 85%, 100% and 100% respectively, compared with 44%, 50% and 83% for bicycle ergometry. For CAD diagnosis, Iliceto et al found a sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 95% with echocardiography following bicycle exercise and 90% and 84% during TAP; in patients with significant CAD but without wall motion abnormalities at rest, sensitivity was 75% during pacing and 56% after exercise. For echo diagnosis of CAD, deCock et al found TAPtest to be more accurate (sensitivity 81%, specificity 100%) as compared to exercise stress testing (62% and 89%). Santomauro et al, Primeau et al, Cuocolo et al have all compared results from myocardial scintigraphy during both TAP and treadmill exercise and found no significant differences between the two provocative tests for ischemia. LeFeuvre et al found sensitivity and specificity of scintigraphy to be 83% and 71% with treadmill exercise, and 94% and 78% using TAP as the stress agent.

TAPtest vs. pharmacologic stress.

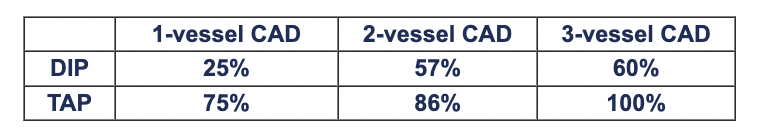

For non-exercise cardiac stress during echocardiography or scintigraphy, TAP is an alternative to pharmacologic agents such as dobutamine, adenosine, dipyridamole. Several studies have indicated that positive-test sensitivity is higher with TAP as compared to dobutamine or dipyridamole: For echo stress diagnosis of single-vessel CAD using submaximal exercise, dipyridamole, dobutamine and TAP, Schroder et al found sensitivities of 47%, 65%, 71%, and 82%. Memmola et al found stress echo with TAP to have sensitivity of 72% for single- and 92% for multi-vessel CAD, while Elhendy et al found dobutamine stress echo to have sensitivity of 56% for single-vessel CAD. In 80 patients undergoing non-exercise stress echo with dipyridamole or TAP, Marangelli et al reported the following sensitivities for 1, 2 and 3-vessel CAD:

Marangelli et al also reported a high rate of side effects with dipyridamole, resolution of which required administration of aminophylline, nitroglycerin or intravenous nitrates; in contrast, ischemia induced via TAP regressed immediately following stimulation. Primeau et al found no differences between efficacy of dipyridamole and TAP for cardiac stimulation during myocardial perfusion imaging. At Mayo Clinic, Pellikka et al administered stress echo tests with both TAP and dobumatine to each of 100 patients and concluded that TAPtest is a “feasible, well-tolerated alternative to dobutamine stress echocardiography. It can be performed rapidly and shows good agreement with dobutamine stress echo in the induction of myocardial ischemia.” The primary advantages of TAPtest over dobutamine were more reliable capture of target heart rate and reductions in both procedure time and side effects (e.g. dysrhythmias).

How do the varying cardiac stress agents compare with respect to myocardial oxygen consumption and induction of ischemia?

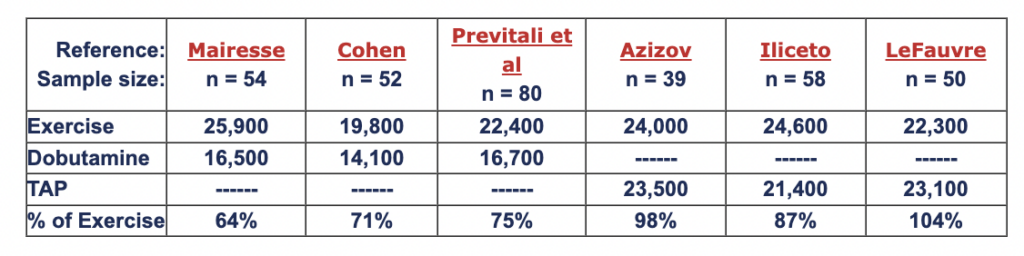

Rate-pressure product (RPP = heart rate x blood pressure, BPM-mmHg) is a work index which is correlated with myocardial oxygen consumption (Gobel et al, Cohen et al). Summarized below are 6 studies comparing RPP measured in the same patients at peak levels of exercise vs. dobutamine and exercise vs. TAP. Compared to dobutamine, TAP induces myocardial oxygen consumption which is closer to that seen at peak exercise.

Abstracts: Mairesse, Cohen, Previtali et al, Azizov, Iliceto, LeFauve

Abstracts: Mairesse, Cohen, Previtali et al, Azizov, Iliceto, LeFauve

In a head-to-head comparison of echo stress testing with TAP and dobutamine in 35 patients, Pellikka et al detected a greater number of ischemic segments with TAPtestas compared to dobutamine (62% vs. 42%), which may be due to the higher heart rates induced at peak stress with TAP (144 vs. 123 BPM).

How should the electrodes be positioned in the esophagus for atrial pacing?

Threshold current for successful “capture” varies with the distance between the esophageal electrodes and atrial myocardium (typically 5-12 mm). Optimal depth of catheter insertion can be estimated with a formula based upon patient’s height or by maximizing the P-wave of the esophageal ECG. (See Positioning Electrodes)

What stimulus current is needed for atrial pacing from the esophagus?

The threshold current for atrial pacing varies with positioning of esophageal electrodes and patient body size. With proper positioning (above), atrial pacing is achieved with currents between 5-25 mA (Roth et al, Atlee et al, Benson et al, Buchanan et al).

What are the hemodynamic responses to transesophageal atrial pacing?

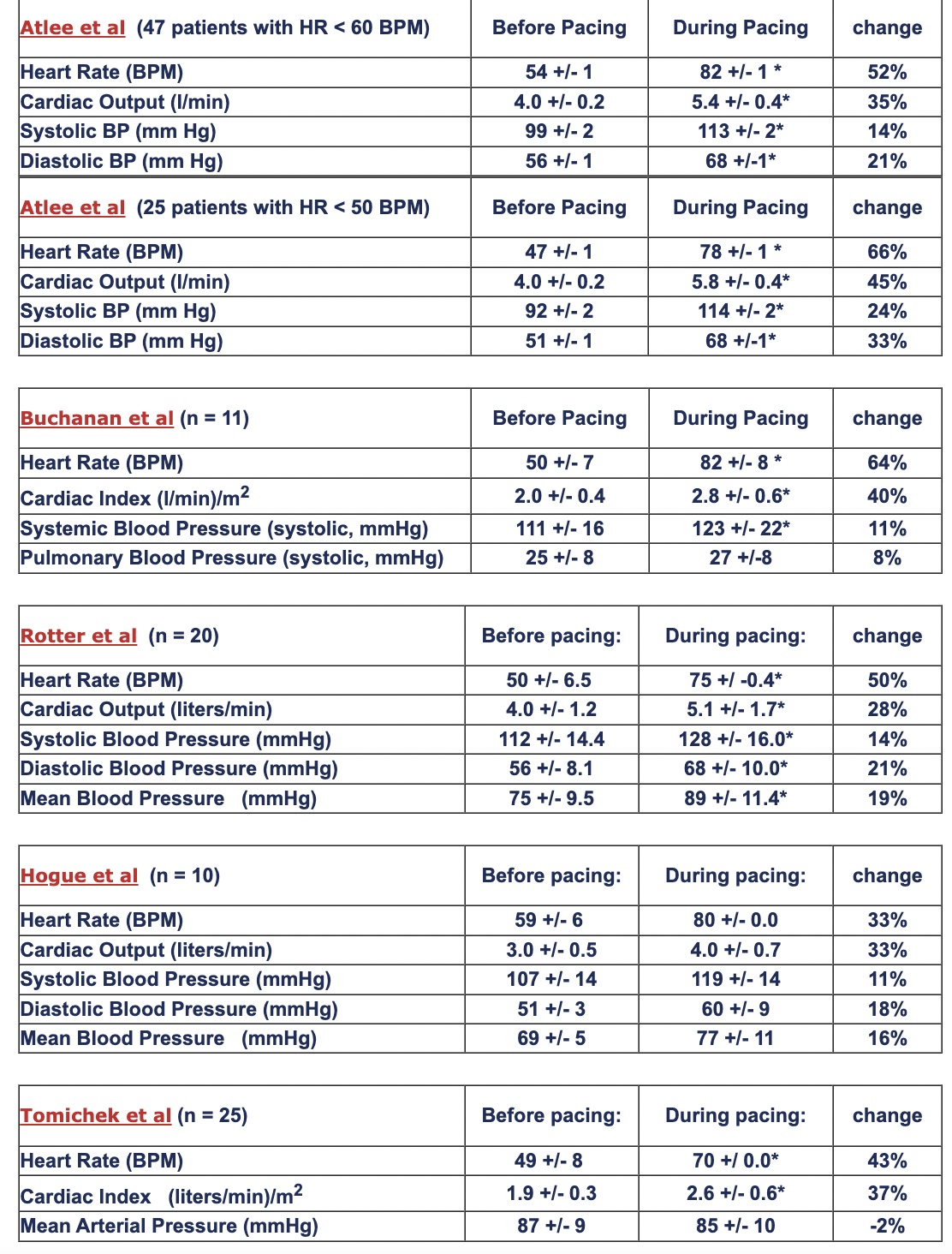

While TAP is predominantly a chronotropic therapy, heart rate acceleration during pacing also produces elevated cardiac output and blood pressure. The 6 tables below summarize hemodynamic responses to TAP for treatment of intraoperative bradycardia:

Abstracts: Atlee et al, Atlee et al, Buchanan et al, Rotter et al, Hogue et al, Tomichek et al

For anti-tachycardia pacing, what rates (beats/min) or cycle lengths (CL, msec) are effective for cardioversion of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) or atrial flutter? (Note: CL = 60,000/pacing rate.)

In 13 pediatric patients, Butto et al cardioverted 48 of 51 flutter episodes to sinus or junctional rhythm using TAP with a CL of 50-100 msec less than the flutter CL; 10/48 episodes transiently converted to atrial fibrillation lasting 3 sec to 28 minutes before spontaneous conversion to sinus junctional rhythm.

For overdrive suppression of atrial flutter in children, Campbell et al compared esophageal and intracardiac rapid atrial pacing using a CL fixed at 72% of the flutter CL, with success rates of 73% and 63%, respectively.

In 49 patients with atrial flutter, Kantharia et al applied TAP at a rate set at 41% higher than the flutter rate and achieved immediate sinus rhythm (35%), delayed sinus rhythm (27%), atrial fibrillation (22%), for an overall successful conversion rate of 84%.

In a literature review, Jadvar & Arzbaecher found atrial pacing with a CL of 72% to 78% of the atrial tachycardia CL to be effective at terminating SVT. The authors recommend a 7-step algorithm for transesophageal cardioversion of atrial flutter:

1) Position electrodes at the atrial level via standard method (Positioning Electrodes).

2) Determine flutter CL from the esophageal electrocardiogram.

3) Adjust stimulator pulse width to 10 msec and current amplitude to 15-20 mA.

4) Adjust pacing cycle length to 90% of flutter CL.

5) Apply burst pacing for 10-20 sec and stop.

6) If cardioversion does not occur, decrease CL by 10 msec and repeat step 5 until:

a) CL = 100 msec (pacing rate = 600 beats/min),

b) successful cardioversion to sinus rhythm,

c) cardioversion to atrial fibrillation, or

d) atrial refractoriness occur.

7) An increase in current amplitude by 5 mA to maximum tolerable by patient may be

warranted if refractoriness develops. From: Temporary Esophageal Pacing, Jadvar H. & Arzbaecher R. in: Temporary Cardiac Pacing. Bartecchi, Mann (editors), Precept Press, Chicago. 1990

What factors improve the rate of successful transesophageal cardioversion?

Normal-size left atria (Giardot et al, Potapenko et al, Chabert et al),

Tachyarrhythmias with more recent onset (Giardot et al, Chabert et al, Guarnerio et al),

Atrial flutter having longer cycle lengths (Doni et al, Zubrin et al),

Pre-administration of antiarrhythmia drug (e.g. propafenone often prolongs flutter CL) (Doni et al, Rhodes et al, D’Este et al, Matiouchine et al, Potapenko et al).

What are reimbursement codes and fee schedules for procedures with TAP?

Can transesophageal atrial pacing cause mucosal injury to the esophagus?

There are no cases published in the medical literature or reported to CardioCommand, Inc. of esophageal injury associated with transesophageal atrial pacing. Nevertheless, it is advisable that patients not be paced for greater than 1 hour.

CardioCommand Transesophageal Cardiac Stimulators are voltage limited at 80V, which restricts output energy to a maximum of .032 Joules/pulse. Investigators have used high-energy transesophageal electrostimulation (20-100 Joules/pulse) for successful atrial and ventricular defibrillation in both animal experiments and human clinical trials without serious complications. These studies indicate the risk for esophageal injury is negligible with low-energy, temporary atrial pacing (Cohen et al, McNally et al, McKeown et al, Cochrane et al, Montoyo et al, Yamanouchi et al, Yunchang et al).